ART TATUM

(October 13, 1909 – November 5, 1956)

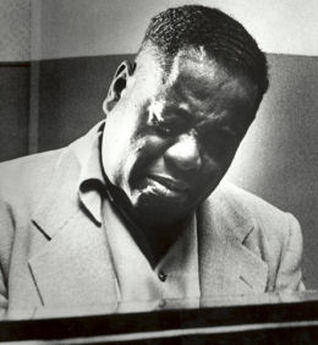

Idolized by jazz instrumentalists and lauded by musicians such as Vladimir Horowitz and composer George Gerschwin, jazz pianist Art Tatum possessed a name synonymous with genius. Like trumpeter Louis Armstrong, Tatum had an impact on the entire strata of jazz instrumentation. As A.B. Spellman observed in the liner notes to Giants of Jazz, Art Tatum, Tatum was "blessed with fingers that moved almost as fast as his endless stream of ideas." Tatum's repertoire consisted primarily of a few original compositions, popular songs, jazz standards, and concert music pieces by such composers as Antonin Dvorak and Jules Massenet. Despite gaining popularity with a trio during the 1940s, Tatum's numerous solo performances still awe listeners and represent some of the finest music of the twentieth century America.

Arthur Tatum, Jr. was born partially blind on October 13, 1909, in Toledo, Ohio. Tatum's father, Art Sr., a mechanic, and his mother, Mildred Hoskins, were members of the Grace Presbyterian Church. Art Sr. played the guitar and Mildred played the piano. Family members later recalled three year old Tatum playing melodies on piano. Tatum studied violin and later, around age 13, took up the piano. He learned to read Braille at Toledo's Jefferson School. In 1924, 15-year-old Tatum attended The School For the Blind in Columbus. As Tatum's biographer, James Lester, asserted in Too Marvelous For Words, "Clearly, the Tatums wanted to do everything they could for their son, and the move to Columbus was made easier by the fact that a cousin was there who would keep tabs on him." In 1925 Tatum enrolled at the Toledo School (Conservatory) of Music where he studied with a classically trained African American instructor, Overton G. Rainey. At home he listened to a wide range of music including jazz piano rolls and recordings of concert pianists.

With end of his formal education in 1927, 16-year-old Tatum embarked on a professional music career in the jazz idiom which offered creative and lucrative opportunities. As Lester wrote, "Within jazz [Tatum] could improvise a career, make a career out of improvising, invent a path for himself, take advantage of fast-changing musical developments, and even influence the course of those developments." He first played in local dance bands, and around 1927 won a local amateur contest which led to his regular appearance on Toledo radio station WSPD. The broadcast was eventually picked up nationally on NBC Blue Network. Tatum's weekday fifteen-minute show sometimes featured his playing duets with another young pianist, Teddy Wilson. In the liner notes to Giants of Jazz, Art Tatum, Wilson recounted that Tatum already employed, "flatted fifths and all the added tones, and improvising these wonderful progressions in the middle of a tune....No other pianist had, even remotely, that conception of playing."

With end of his formal education in 1927, 16-year-old Tatum embarked on a professional music career in the jazz idiom which offered creative and lucrative opportunities. As Lester wrote, "Within jazz [Tatum] could improvise a career, make a career out of improvising, invent a path for himself, take advantage of fast-changing musical developments, and even influence the course of those developments." He first played in local dance bands, and around 1927 won a local amateur contest which led to his regular appearance on Toledo radio station WSPD. The broadcast was eventually picked up nationally on NBC Blue Network. Tatum's weekday fifteen-minute show sometimes featured his playing duets with another young pianist, Teddy Wilson. In the liner notes to Giants of Jazz, Art Tatum, Wilson recounted that Tatum already employed, "flatted fifths and all the added tones, and improvising these wonderful progressions in the middle of a tune....No other pianist had, even remotely, that conception of playing."

Tatum's employment in Toledo speakeasies and premiere nightclubs allowed him to work out the music he had formally learned by instruction and by listening to records and radio. Even as a teenager Tatum astounded fellow musicians. Noting Tatum's impact on musicians, Benny Green stressed in The Reluctant Art, "Tatum shattered everyone; Tatum caused all other musicians to lose confidence; Tatum terrified those who thought they knew how far jazz could be taken." In 1929, the "father of the tenor saxophone" Coleman Hawkins, then a member of Fletcher Henderson's Orchestra, heard Tatum at a small Toledo club and immediately incorporated the pianist's harmonic ideas into his playing. Around this time, Duke Ellington encountered Tatum in Cleveland and encouraged him to move to New York City.

Tatum went to New York City in 1932 as the accompanist for singer Adelaide Hall. He recorded four sides with Hall and toured with her, until landing jobs as a solo pianist in New York City. "His first visit to New York," recounted Duke Ellington in his memoir, Music is My Mistress, "stirred up quite a storm. In a matter of hours, it got to all piano players--and musicians who played other instruments, too--that a real Bad Cat had arrived...." Not long after his arrival, Tatum agreed to meet Harlem's three leading pianists--James P. Johnson, Willie "The Lion" Smith, and Fats Waller--at Morgan's, a Harlem bar with a suitable piano. Pitted in a piano battle against these musical giants, Tatum overwhelmed his challengers. Looking back on that evening Waller confessed, as quoted in Fats Waller, "That Tatum, he was just too good....He had too much technique. When that man turns on the powerhouse don't know one play him down. He sounds like a brass band." Tatum had bested his rivals and thus established himself as one of the greatest pianists on the New York City jazz scene.

Tatum went to New York City in 1932 as the accompanist for singer Adelaide Hall. He recorded four sides with Hall and toured with her, until landing jobs as a solo pianist in New York City. "His first visit to New York," recounted Duke Ellington in his memoir, Music is My Mistress, "stirred up quite a storm. In a matter of hours, it got to all piano players--and musicians who played other instruments, too--that a real Bad Cat had arrived...." Not long after his arrival, Tatum agreed to meet Harlem's three leading pianists--James P. Johnson, Willie "The Lion" Smith, and Fats Waller--at Morgan's, a Harlem bar with a suitable piano. Pitted in a piano battle against these musical giants, Tatum overwhelmed his challengers. Looking back on that evening Waller confessed, as quoted in Fats Waller, "That Tatum, he was just too good....He had too much technique. When that man turns on the powerhouse don't know one play him down. He sounds like a brass band." Tatum had bested his rivals and thus established himself as one of the greatest pianists on the New York City jazz scene.

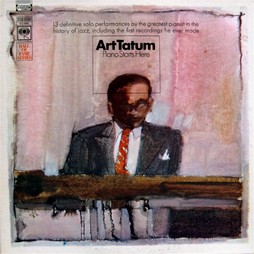

In 1933, Tatum played the Onyx Club on 52nd Street. In March of that same year, he recorded his first official solo session, which included "Tiger Rag," "Tea For Two," "St. Louis Blues," and Duke Ellington's "Sophisticated Lady." In assessing these first sides recorded for the Brunswick label, Leonard Feather, in the liner notes to Art Tatum, Piano Starts Here, observed "The characteristics that were to remain Tatum's trademarks until the day he died were already evident: the incessantly creative left hand, now striding, now playing four different chords to the bar; the use of substitute chords and unprecedented harmonic subtlety; the sixteenth note runs at tempos that gave most pianists trouble maintaining an even flow of eighth notes."

In August and September of 1934, Tatum returned to the studio, and in the following year, without steady work in New York City, he performed in Cleveland. In 1935 he performed on the "Fleischman Hour" radio program hosted by Rudy Valee. He also played the Three Dueces in Chicago, and eventually formed a quartet at the club. After the end of his stint at the Three Deuces in 1936, Tatum traveled to Los Angeles, where his reputation had already been established. He played Hollywood parties and venues like the Tracadero, Paramount, and the Club Alabam on Central Avenue in the heart of Los Angeles's black entertainment scene. After several months in Los Angeles Tatum returned to New York City in 1936, and then, during the following year, returned to the west coast and recorded with a group, Art Tatum and His Swingsters. In 1937 he also recorded for the Brunswick label in New York City, producing the numbers "Stormy Weather," "The Sheik of Araby," "Chlo-e," and "Gone With the Wind."

In 1938, Tatum left for England on the Queen Mary, and played a three month engagement in various English clubs and appeared on the BBC. As Lester explained in Too Marvelous For Words, "Art's appearances in England were not concerts," but the quiet attentiveness of the audiences "made them something closer to concerts than anything Tatum had experienced at home." By 1938 Tatum's music began to be transcribed and notated in publications, and his bookings resulted in residencies at various clubs. His recordings for Decca included Jules Massenet's "Elegie" (1938) and eighteen numbers in 1939, including "Get Happy" and Atonin Dvorak's "Humoresque." His 1940 output for Decca included a more popular version of "Humoresque," "Cocktails For Two," and "Begin the Beguine."

Between 1939 and 1940, Tatum worked in New York City and made frequent trips to Los Angeles where he made seventeen sides for Decca. A recently issued live recording, Art Tatum, California Melodies, captures the pianist in a series of Los Angeles (KHJ) broadcasts that aired from April to July of 1940. Tatum's recordings from this weekly program "is perhaps the most valuable and historically important addition to [Tatum's] recorded legacy," noted Stephen C. LaVere in the liner notes to California Melodies.

Between 1939 and 1940, Tatum worked in New York City and made frequent trips to Los Angeles where he made seventeen sides for Decca. A recently issued live recording, Art Tatum, California Melodies, captures the pianist in a series of Los Angeles (KHJ) broadcasts that aired from April to July of 1940. Tatum's recordings from this weekly program "is perhaps the most valuable and historically important addition to [Tatum's] recorded legacy," noted Stephen C. LaVere in the liner notes to California Melodies.

During January of 1941, Tatum recorded a Decca session under the title Art Tatum and His Band, a small pickup group including blues vocalist Joe Turner. The session produced four numbers including the big-selling number, "Wee Wee Baby Blues." The success of "Wee Wee Baby Blues" prompted another recording session with Turner, and in June of 1941, four sides were cut, including "Corrine Corina." His next commercial recordings did not emerge until 1943, when he won Esquire's first jazz popularity poll. Without steady bookings as a solo artist, Tatum looked to other opportunities to support himself; in 1943, he formed a trio with guitarist Tiny Grimes and bassist Leroy "Slam" Stewart. The trio, observed Lyons in The Great Jazz Pianists, "was celebrated for the inventive communication among the players as well as for Tatum's blistering speed, as they achieved a unity of sound that was rare at any tempo." Tatum's 1944 recordings were entirely made up of his trio work. During 1945, he appeared on the radio, attended only two studio sessions, and finally decided to quit working in a trio format.

At end of the Second World War in 1945, observed Lester in Too Marvelous For Words, Tatum's "standing and reputation were established beyond challenge, but his popularity," primarily due to the emergence of bebop, "faded seriously in the remainder of the 1940s." Tatum's music did not follow this modernist jazz trend, but it did have profound influence on its leading musicians, like Charlie Parker who, for one year, washed dishes in a Harlem restaurant just to listen to Tatum's playing in the front room, and bebop piano genius Bud Powell idolized the keyboard master from Toledo.

San Francisco’s Black Hawk Club

In the spring of 1949, Tatum performed at Los Angeles' Shrine Auditorium. That same year, Tatum signed with Capitol Records and recorded several critically acclaimed numbers. He made his concert stage debut in 1945, and subsequently played a circuit of university and community halls across the country, while continuing to play club and concert dates into the mid-1950s, including San Francisco's Black Hawk Club in 1955, and the Hollywood Bowl in August 1956.

In 1953, Tatum signed with Norman Granz's Clef/Verve label, for which he recorded over 120 piano solos. Discussing Tatum's recorded repertoire that included many of the same selections, Lyons, noted that, even during the 1950s, he "rarely repeated himself in his treatment of material. His harmonic variations were startling, especially when he soloed. Where another pianist might go directly from one chord to the next, Tatum's left hand would walk crablike through a cycle of four to six new chords between the original two. Meanwhile, his right hand would spin out a web of interconnecting lines of thirty-second notes."

In 1953, Tatum signed with Norman Granz's Clef/Verve label, for which he recorded over 120 piano solos. Discussing Tatum's recorded repertoire that included many of the same selections, Lyons, noted that, even during the 1950s, he "rarely repeated himself in his treatment of material. His harmonic variations were startling, especially when he soloed. Where another pianist might go directly from one chord to the next, Tatum's left hand would walk crablike through a cycle of four to six new chords between the original two. Meanwhile, his right hand would spin out a web of interconnecting lines of thirty-second notes."

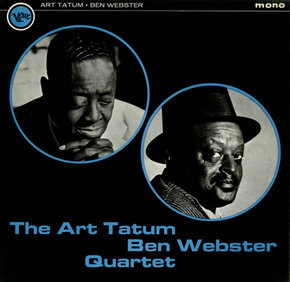

Apart from his solo recordings, the Verve label recorded Tatum in several small group settings with jazzmen such as Benny Carter, clarinetist Buddy DeFranco, vibraphonist Lionel Hampton, and tenor saxophonist Ben Webster. His session with Webster, recorded in September of 1956, is considered by most critics as the finest of these small group recordings. In his review of The Art Tatum-Ben Webster Quartet for Jazz Review, critic Dick Katz, stated, as reprinted in the book Jazz Panorama, how "Tatum's and Webster's respective conceptions complement each other beautifully....Art Tatum and Ben Webster represent to me a kind of romanticism in jazz which has now itself become classic. Theirs is an artistry rarely matched in any era of jazz."

But this session would be Tatum's last. For years Tatum, a heavy beer drinker, had, later in his life, suffered from diabetes. By the mid-1950s, he fell ill with uremia. He died in Queens Hospital in Los Angeles, on November 5, 1956. In tribute to the keyboard master, Leonard Feather wrote, in the liner notes to Art Tatum the Piano Starts Here, "How many frustrations Tatum had to suffer during his forty six years, none of us can ever quite know. He was black in a society that awarded honors to white musicians with a tenth of his talent." But Tatum's legacy is one of a committed brilliant musician. Not long after Tatum's death, Benny Green, wrote in his collected work of essays, The Reluctant Art, that "Tatum has been the only jazz musician to date who has made an attempt to conceive a style based upon all styles, to master the mannerisms of all schools and then synthesize those into something personal." In the liner notes to Giants of Jazz, Art Tatum, Spellman also emphasized that "Tatum conceived a style based on all styles...No one more than Tatum summarized the art of his generation, and no one more than he pointed the way to the generation of pianists who followed him."

Click here to return to the Let My People Swing! main page.